(Blogtober Day 3)

I’ve been a several narrative design and writing for games talks, and I have read over a dozen books covering the same topics, and I’m always amazed how, in my opinion, how little narrative design is actually ever discussed in any of them. There is often focus on writing, and branching dialogues trees, and occasionally a discussion about how a project achieved having multiple endings. Lots of inspired chats about things narrative designers and writers would like to try in a game, or how to avoid tropes in character design. But almost nothing regarding story/narrative design structure or systems.

I’m not sure why this is, but it has been something I have wondered about for a very long time. I suspect it likely has to do with story and narrative rarely being the very top priority focus in a game’s development, and in many cases it probably shouldn’t be. But even taking that into consideration, having a clear understanding of how a narrative design takes shape, beyond the words, I think it important to be able to innovate. So I wanted to use a few of these Blogtober posts to try to roughly define some of the structures I have used and seen used in my career and gaming experiences starting with the most straightforward design I think there is.

A Straight Line Design

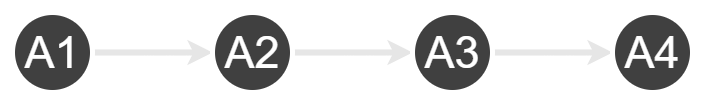

The remarkable simplicity of this design structure is both its strength and largely its weakness. In a straight line narrative design the player is guided and directed from one story beat to the next without deviation. One story moment leads to the next which leads to the next. The narrative world building is also provided to the player in the same beats. The characters are introduced in the same beats. And so on, and so on.

What’s Good About It

This is linear storytelling. Its direct. While it is broken up into beats, at any given point the player will be at an exact position in the story. While a human player will always be an element of unknown chaos in terms of what or how they progress in a game, with a straight line design you will always have progression markers for what they player knows, what NPCs they have met, what story beats they have experienced, and so forth. The variables are reduced and easier to plan for.

While you can still take the player on a narrative journey through something like a 3 act structure, with challenges they must overcome or twists, you know when and if they have happened.

Does the player know who Professor Lorum is? If Professor Lorum is introduced in story beat A1, and the player has progressed to story beat A3, then yes. Because the player had to learn about Professor Lorum in order to get to beat A3.

What’s Bad About It

The biggest criticism for straight line narrative is that it, by design, removes player agency when experiencing the story. Players are essentially forced in one direction. One player might take longer to get from beat A1 to beat A3 than another, but they will always pass the same stops, in the same order, on their way to the same destination. And that’s fine! There are some genres of games, particularly ones that do not focus on a story, where this simplicity is desired. And in much larger and more complex narrative structure designs there are still going to be at least some sections that are still a straight line.

But in the modern gaming world where player choice and agency (or the illusion there-of) are key selling points, too much of a straight line structure might be recognized and seen as a drawback from the overall offering.